Russell and President Lyndon B. Johnson circa 1967.

Richard B. Russell, Jr. was born just outside Winder, Georgia, on November 2, 1897 to Richard B. Russell, Sr. and Ina Dillard Russell. A politically active family, the Russells maintained high expectations for their children and encouraged their ambitions. Russell graduated from the Seventh District Agricultural and Mechanical School (later John McEachern High School) in Powder Springs before attending Gordon Institute (now Gordon College) in Barnesville. He also earned a Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of Georgia.

Following a stint in the U.S. Naval Reserve, Russell returned to Winder in 1919 to practice law. Running as a Democrat, Russell won a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives in 1920 to become one of Georgia’s youngest legislators. He spent ten years in the statehouse—the last four as Speaker. As a legislator, Russell sought to build new roadways, improve public education, reduce the influence of special interests, and operate government in a fiscally conservative manner. In 1930, voters elected him, at age 30, Georgia’s youngest governor in the twentieth century. As governor, he completed a comprehensive reorganization of state government, reduced state spending, and balanced the budget.

Senator William J. Harris’s death in 1932 opened the door for Russell’s entry into national politics. After appointing an interim, Russell defeated U.S. Representative Charles Crisp and became a U.S. senator in 1933. A supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Russell earned a coveted spot on the Senate Appropriations Committee where he helped pass several New Deal programs. He remained a member of the Appropriations Committee as well as the Armed Service Committee throughout his time in the Senate. Fittingly, Russell ended his long public service career as President pro tempore, making him third in the line of presidential succession.

Russell committed himself to learning the rules, regulations, precedents, history, customs and traditions of the U.S. Senate. Although a skilled debater, he often avoided speaking on the Senate floor. Working primarily behind the scenes, Russell’s Senate career was dominated by his role in shaping America’s national security apparatus after World War II, his dedication to the public welfare, and his opposition to civil rights legislation.

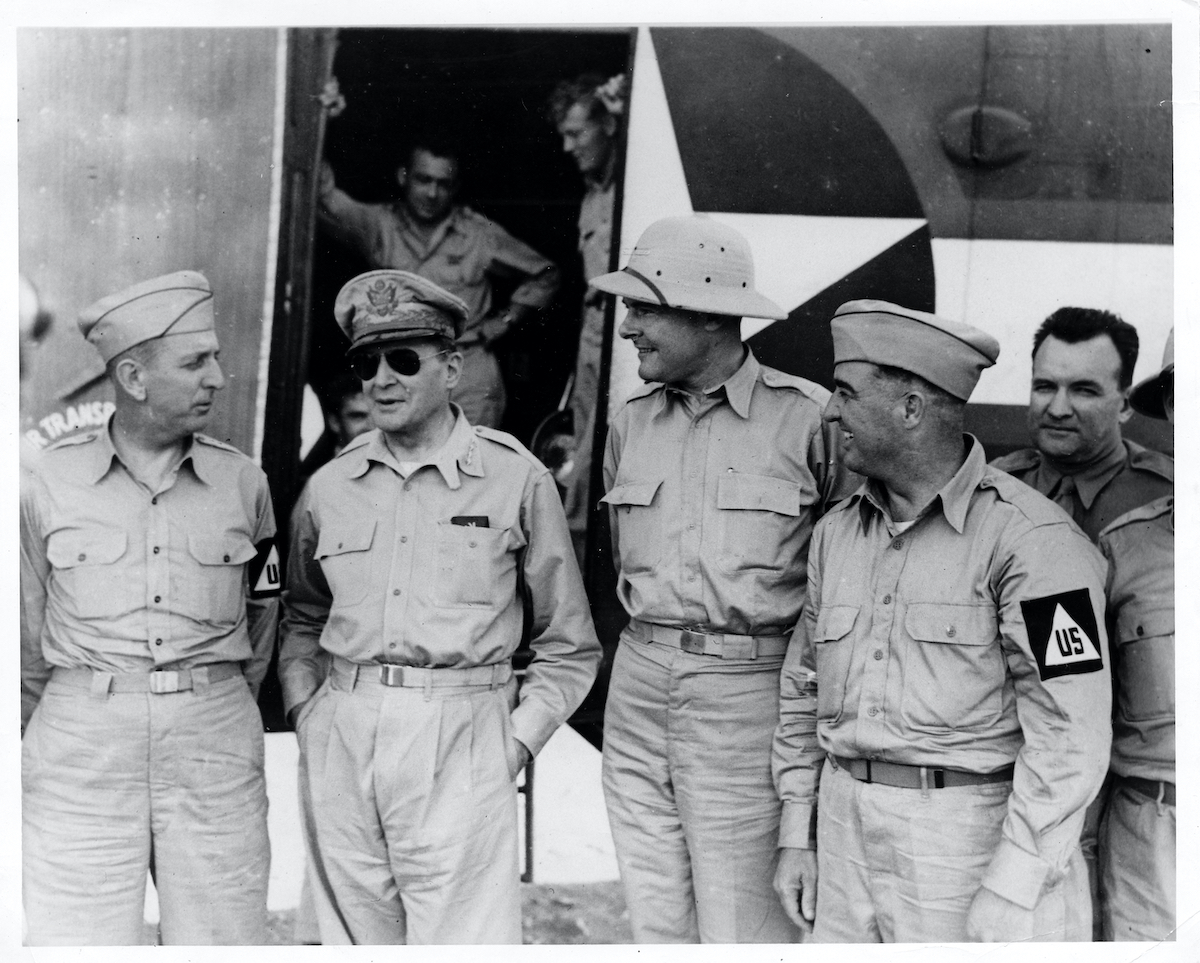

Russell supported a large military buildup throughout the Cold War, but he insisted upon civilian oversight. As chair of the Armed Services Committee, he helped establish the Military Preparedness Subcommittee, Atomic Energy Commission, Central Intelligence Agency, and joint civilian-military control of space exploration.

Russell generally favored military force only when the nation’s interests were under direct threat. Russell advocated military action during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 because he considered Soviet military activity on the island a breach of the longstanding Monroe Doctrine. On the other hand, Russell spoke out in 1954 against American military intervention in French-controlled Vietnam. As American involvement in Vietnam escalated throughout the 1960s, Russell advised presidents to "go in and win—or get out." Despite his frustrations, Russell supported American troops in Vietnam by monitoring and ensuring defense appropriations.

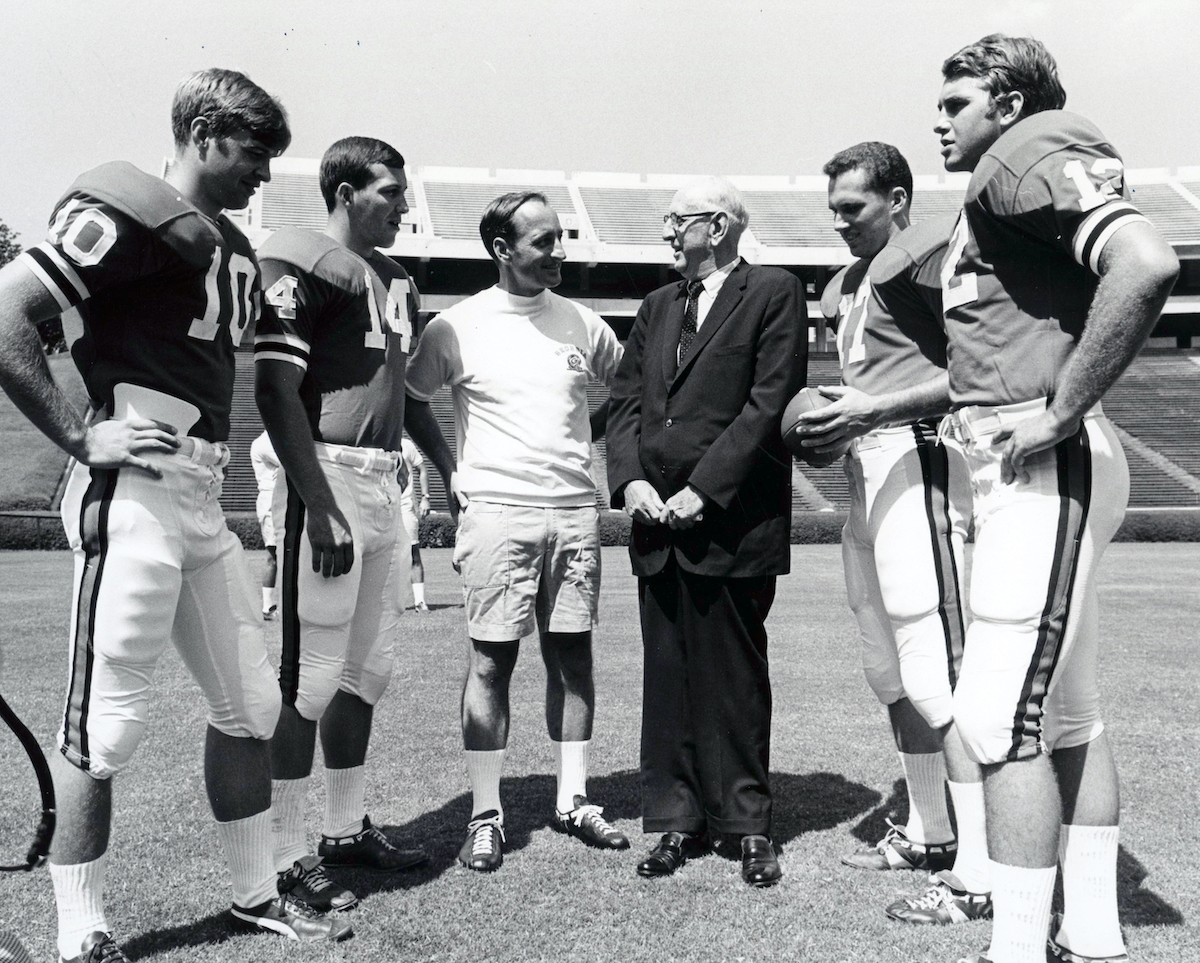

Believing firmly that he was elected to represent Georgia’s interest in Washington, not Washington’s interest in Georgia, Russell worked tirelessly to bring federal dollars to Georgia. He secured fifteen military installations and over twenty-five research facilities—including the Centers for Disease Control and the Russell Agricultural Research Center—during his Senate career. Russell, who had supported the use of farm surpluses to upgrade school lunches since 1935, argued that the National School Lunch Act of 1946 represented his most significant achievement. Russell also helped establish the forerunner of the food stamp program.

Russell wielded his mastery of Senate rules and procedure to devastating effect on the issue of civil rights. Couching his segregationist stance in terms of Jeffersonian republicanism and states’ rights, Russell defended the white South’s traditions and values without engaging in the racial demagoguery of that era. A leader of the “Southern Bloc,” Russell helped stall, weaken, and defeat federal civil rights legislation in the Senate for over three decades.

By 1964, though, the tide had turned against Russell and the Southern Bloc. With the backing of President Lyndon Johnson, Russell’s friend and former protégé, the Senate overcame the stalling tactics to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Russell had opposed the bill, but he urged compliance and counseled against violence or forcible resistance.

An undisputed patriarch of the Senate, Russell remained a product of his generation and of a segregated society that privileged white above non-white, and he failed to remove barriers that held black and white Americans captive in the tragedies of the past. Russell’s unyielding opposition to civil rights legislation proved costly to the nation and to Russell personally. It derailed his 1952 presidential campaign, diverted him from other important business, weakened his health, and inflicted lasting damage to his reputation and legacy.

Russell died of complications from emphysema at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C., on January 21, 1971. He is buried in the Russell Memorial Park behind the Russell family home in Winder, Georgia.

Ultimately, Richard B. Russell, Jr.’s legacy is complex and complicated—not unlike the man himself. He held public office for fifty years as a state legislator, governor of Georgia, and United States senator. A record of mastering arcane Senate rules and procedure, strengthening the national defense, protecting rural, agricultural interests, building and strengthening the public welfare system, and, regretfully, opposing civil rights legislation defined Russell’s public service career.

Russell, the consummate “senator’s senator,” served in that body from 1933 until 1971. In that time, Russell earned the respect and admiration of Senate friends and foes alike. Following his death, his former colleagues renamed his old office building the Richard Brevard Russell Senate Office Building to memorialize Richard Russell’s collegiality, legislative prowess, and lifetime of public service.

Further Reading

Boney, F.N. " `The Senator's Senator': Richard Brevard Russell, Jr., of Georgia.'' Georgia Historical Quarterly 71 (Fall 1987): 477-90.

Campbell, Charles E. Senator Richard B. Russell and My Career as a Trial Lawyer: An Autobiography. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2013.

Day, John Kyle. The Southern Manifesto: Massive Resistance and the Fight to Preserve Segregation. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2014.

Fite, Gilbert C. "The Education of a Senator: Richard B. Russell, Jr., in School.'' Atlanta Historical Journal 30 (Summer 1986): 19-31.

_____. Richard B. Russell, Jr., Senator From Georgia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

_____. "The Richard B. Russell Library: From Idea to Working Collection.'' Georgia Historical Quarterly 64 (Spring 1980): 22-34.

_____. "Richard B. Russell and Lyndon B. Johnson: The Story of a Strange Friendship.'' Missouri Historical Review 83 (January 1989): 125-38.

Gay, James Thomas. "Richard B. Russell and the National School Lunch Program." Georgia Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 1996): 859-72.

Goldsmith, John A. Colleagues: Richard B. Russell and His Apprentice, Lyndon B. Johnson. Washington: Seven Locks Press, 1993.

Grant, Philip A. "Editorial Reaction to the 1952 Candidacy of Richard B. Russell.'' Georgia Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1973): 167-78.

Hale, F. Sheffield. "Richard B. Russell's Election to the Senate: The Watershed of Two Political Careers.'' Atlanta Historical Journal 28 (Spring 1984): 5-21.

Mann, Robert. The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell and the Struggle for Civil Rights. New York: Harcourt Brace Co., 1996.

Mead, Howard N. "Russell vs. Talmadge: Southern Politics and the New Deal.'' Georgia Historical Quarterly 65 (Spring 1981): 28-45.

Mellichamp, Josephine. "Richard B. Russell, Jr.'' In Senators from Georgia, pp. 245-60. Huntsville, AL: Strode Publishers, 1976.

Potenziani, David D. "Striking Back: Richard B. Russell and Racial Relocation.'' Georgia Historical Quarterly 65 (Fall 1981): 263-77.

Russell, Sally. A Heart for Any Fate: The Biography of Richard Brevard Russell, Sr. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004.

_____. Richard Brevard Russell, Jr: A Life of Consequence. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2011.

Stern, Mark. "Lyndon Johnson and Richard Russell: Institutions, Ambitions and Civil Rights.'' Presidential Studies Quarterly 21 (Fall 1991): 687-704.

U.S. Congress. Memorial Services in the Congress of the United States and Tributes in Eulogy of Richard Brevard Russell, Late a Senator from the State of Georgia. 92d Cong., 1st sess., 1971. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1971.

U.S. Congress. Senate. Dedication and Unveiling of the Statue of Richard Brevard Russell, Jr. Proceedings in the Rotunda of the Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC, January 24, 1996. 105th Cong., 1st sess., 1997. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1997.

Vogt, Sheryl B. A Guide to the Richard B. Russell, Jr. Collection. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

_____. “Richard B. Russell, Jr.: Patriarch of the Senate,” in Maxmillian Angerholzer III, James Kitfield, Christopher P. Lu and Norman Ornstein (Center for the Study of the Presidency & Congress) eds., Triumphs and Tragedies of the Modern Congress: Case Studies in Legislative Leadership (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, 2014), pp. 74-80.

Woods, Jeff. Richard B. Russell: Southern Nationalism and American Foreign Policy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007.

Ziemke, Caroline F. "Senator Richard B. Russell and the `Lost Cause' in Vietnam, 1954-1968.'' Georgia Historical Quarterly 72 (Spring 1988): 30-71.